Designing a Laborist Compensation Model: Key Considerations

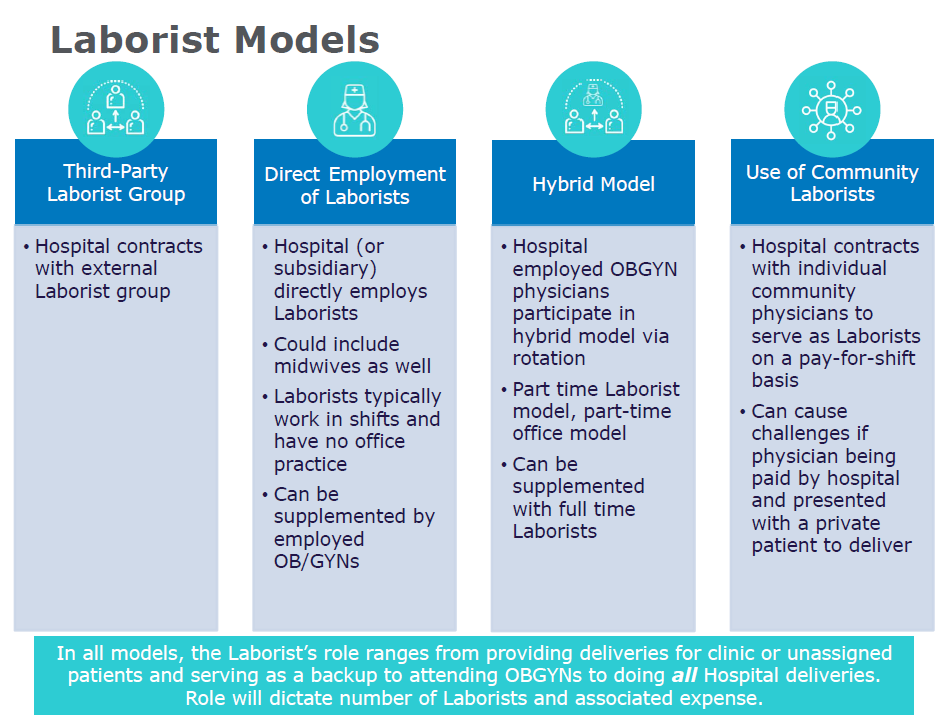

Laborist models continue to gain traction as hospitals seek ways to improve patient safety and professional satisfaction and respond to the national OBGYN shortage. But there are two aspects of the laborist model that hospital leaders often grapple with: reimbursement and compensation.

Many hospitals are shifting from “traditional” management of labor and delivery where each physician (or physician practice) provides labor and delivery care on behalf of their own patients to a system under which hospital-funded laborists (which may be employed, independent contractors, or provided by a specialty services provider company) provide labor and delivery care for all (or some subset of) deliveries at the hospital. Since maternity care is typically reimbursed on a global basis, assuring that those that participated in the care of the patient throughout the process can be challenging. The basic concept is not new – if the hospital (or another group) pays for the laborists, then the hospital must receive compensation or reimbursement for those services and, conversely, another physician cannot receive compensation or other benefit for the services provided by the hospital-funded laborist. Yet, once a laborist model is in place – it’s easy to forget some compensation basics exposing the parties to compliance issues by unwittingly providing a benefit to private attendings, whether financial or benefits of convenience.

Before we dive into the reimbursement and compensation issues and how to avoid them, let’s acknowledge how hard this is.

It’s hard to change a care model. Obstetricians may not want to give up seeing their patients all the way through labor. They also may not trust the laborists – whom they may or may not know – to take good care (both physical and emotional care) of their patients. Hospitals will consider whether they will force this new model on the obstetricians or will we make it optional for them. Then there are many operational details from scheduling to identification of specific responsibilities.

It’s also hard to change a compensation model. Questions arise around: How will we pay the laborists? What level of investment can we afford? How can we bill effectively to assure compensation (or reimbursement) ends up in the right place.

Changing both the care model and the compensation model at the same time can feel daunting. To effect the change, hospital administrators may want to make the new model appealing or make it easy – two goals which could result in letting one’s guard down and result in compliance challenges.

Moving to a Laborist Model of Care and Compensation

At its core, the funds flow model (i.e., the compensation or reimbursement model) must assure that the party doing the work gets paid for doing the work – even if the reimbursement model is not easily set up that way and even if there is no incremental cost to do so.

Consider a scenario where a laborist cares for an independent OBGYN’s laboring patient. The laborist may provide care for a specified amount of time or for a specific service. Examples include: (i) during the middle of the night to allow the independent OBGYN to get a few more hours of sleep; (ii) for only a critical hour until the attending OBGYN arrives to take over; or (iii) the entire labor including delivery. Regardless of the amount of time that the laborist may have spent, the laborist (or the hospital) must be compensated for this time. This also means that the independent OBGYN should not be reimbursed (or retain reimbursement) for care not provided; and if the OBGYN is a hospital-employed physician should not get WRVU credit for work not provided.

Assuring the appropriate compensation can be complicated in a model that is primarily based on a case-rate model which awards payment for the entire course of care – pre-natal through delivery through post-partum. Further, in certain circumstances there may not be any additional costs to have the laborist step in to provide interim care (e.g., the laborist is there to serve the hospital’s clinic patients – so “no worries” if she steps in to support another doctor who hasn’t arrived yet). However, just because there was no incremental cost does not mean that there was no value to the service provided.

Here are three approaches to assure that compensation and reimbursement are handled to assure that hospitals (or laborist groups) are compensated for the work of the laborists that they support and key considerations for each.

Payments between parties. If the OBGYN bills globally for the care, regardless of the amount of time that the laborist may have spent, the laborist (or the hospital) may not also bill for these services. To avoid compliance concerns or inducements to refer, the laborist (or the hospital) must be paid for the services provided. One way to do this is to establish a provider agreement where the OBGYN bills the global service, but also agrees to pay to the laborist (or hospital) a specified fee for services provided (e.g., a specified rate for supervising labor, a specified rate for a delivery, etc.).

Further complicating this structure is the common situation whereby the laborist is an independent group receiving a subsidy from the hospital. They hospital must require a fee be paid by independent OBGYN physicians to its independent laborist group – an arrangement required by the hospital but to which the hospital is not a party. Such fees may be structured on a per-service or per-hour basis. If an hourly basis is selected the parties must develop a way to document hours and may want to set limits on the minimum or maximum number of hours to be paid (as labor time can be unpredictable as many readers of this blog can attest).

Split billing. Although global billing is most prominent, there are separate CPT codes for each component of pregnancy-related services, including prenatal care, delivery, and post-partum care. The parties could agree to bill only the components performed by each – allowing the laborist (or hospital) to capture revenue for the work performed by the laborist.

Under this model, the global case rate per patient is broken down into components by the payers. The problem with this model is that commercial payers may be unwilling to split the global reimbursement. Further, such splitting requires coordination between the two billing parties that collaborated to provide the entire course of care.

A hospital-specified, time-based rate for coverage. Further complicating the scenario above is one that may occur in a laborist care model in which physicians work laborist shifts but also have their own patient panel. Consider a situation where a laborist is working a shift (and being paid an hourly rate by the hospital to do so) and that physician cares for their own patient while working that same shift, billing globally for their own patient. In this case, if the laborist bills globally for the full course of pregnancy, the physician will have been double-paid for that time – paid by the hospital for the laborist-shift coverage and paid by a third-party payer as part of the global payment (or in the case of an employed physician, paid for a laborist shift and also earned WRVU credit for the delivery performed during that shift).

There are a number of ways to fairly handle this situation. One option is to not compensate the physician for time spent caring for their own patients; but perhaps they cared for a second patient at the same time? Another option is to adjust the hourly rate suggest that only a partial payment is made for each hour. For example, let’s say that the fair market value of is $300 per hour, the hospital might set an hourly rate of $200 for laborist coverage to account for the payment the laborist could also receive for working with their own patients during that hour. Alternatively, the arrangement with the laborist could prohibit the physician from delivering their own private patients during their laborist shifts.

Laborists offer a new model for in-hospital delivery care. They provide a level of safety and quality by having a consistent group of physicians readily available to care for patients in labor and through delivery. However, the model by which they interact with other obstetricians can introduce compliance challenges. When implementing a laborist model be sure that all parties are properly paid for the services they provide.

Contact the Authors:

Richard Chasinoff, Director, rchasinoff@veralon.com

Monica Nuñez, Manager, mnunez@veralon.com